By: Tom Di Liberto | Posted: July 8, 2016 | Source: Climate.gov

A tremendous amount of rain fell across central and southern West Virginia and western Virginia during the third week of June. With nowhere to go but into local waterways, many streams, creeks and rivers turned into raging torrents, washing away anything in their paths. The flash floods killed at least 23 people making the event the third deadliest flood in West Virginia history according to news reports citing the West Virginia state climatologist, Kevin Law.

A powerline toppled into Brackens Creek next to a washout of WV Route 60 between Lookout and Hilton Village. Photo by Rebecca Lindsey.

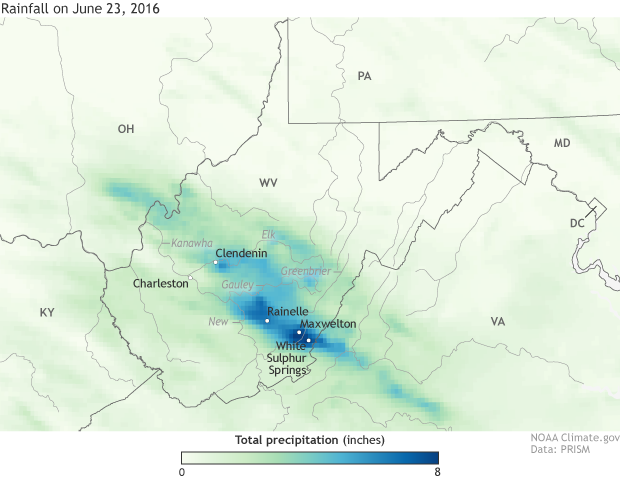

A storm system that initially formed closer to the Great Lakes brought repeated rounds of torrential thunderstorms across the state. Rainfall totals were staggering. In Greenbrier County, West Virginia, Maxwelton received 9.67 inches of rain in the 36 hours leading up to June 24. White Sulphur Springs observed 8.29 inches in 24 hours, doubling the previous record for wettest day (4 inches, set in 1890).

An “early glimpse” of 24-hour rainfall totals from storms over West Virginia on June 23, 2016, based on PRISM data from Oregon State University. “Early glimpse” data may not include data from all stations in the reporting network, and totals should be considered preliminary. Even the preliminary totals are enormous, however, with up to 8 inches of rain in many areas of southeastern West Virginia. Map by NOAA Climate.gov.

National Weather Service radars estimated more than 10 inches in localized parts of Greenbrier County. To the west, in Alleghany County, Virginia, more than 5.5 inches of rain fell near Covington. Much of the rain fell in just 12 hours.

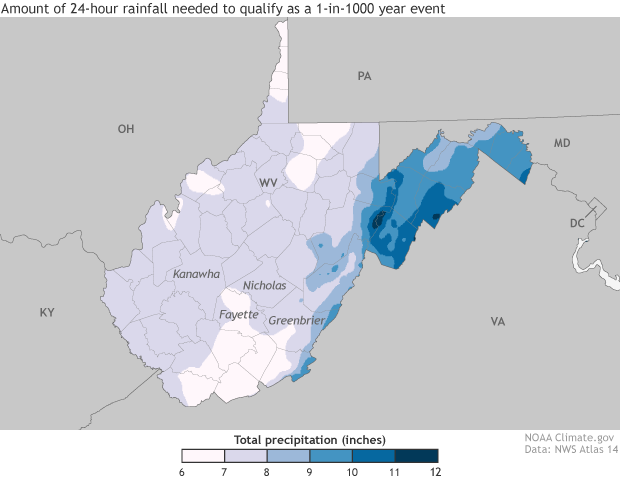

Based on the fixed “day” used by forecasters, the National Weather Service said that 24-hour rainfall amounts in parts of Fayette, Nicholas, and Greenbrier Counties were a “thousand-year event,” meaning there is only a 0.1% chance of an event of this magnitude happening in any given year (stick around for a follow-up post which explains how—given that we don’t have a thousand years of rainfall observations—weather experts make these estimates.) An analysis by Nick Webb, a meteorologist with the Charleston, WV, forecast office, based on the 24-hour period spanning the event, concluded that thousand-year 24-hour rainfall totals were also likely exceeded in parts of Kanawha, Roane, and Clay counties.

The 24-hour rainfall totals that history and statistics indicate would only happen, on average, once every thousand years. According to analysis from National Weather Service meterologists, 24-hour rainfall amounts in parts of Kanawha, Roane (north of Kanawha, not labelled), Clay (east of Kanawha), Fayette, Nicholas, and Greenbrier Counties likely exceeded the 1-in-1,000-year return amounts. NOAA Climate.gov, based on NOAA Atlas 14 data.

As the water rushed into streams and rivers, waters began to rise rapidly. The Elk River at Queens Shoals, West Virginia, rose to over 33 feet, breaking the previous high water record set in 1888. Record or near-record crests also occurred at stations on the Gauley, Meadow, Cranberry, Greenbrier, and New Rivers.

Normally tranquil rivers turned into a violent mash-up of water and whatever else had washed into the streams. In addition to the terrible loss of life, property damage was enormous: bridges and roads washed out, houses destroyed, whole towns inundated.

Aerial footage of flooding in the Greenbrier County town of Rainelle, WV, on June 24, the day after the 1-in-1000 year rainfall event. Video produced by Rob Atha, Elevated Media. Used by Climate.gov with permission. See full length video here.

In one instance, 500 people became stranded in a shopping center as the bridge leading to the shopping center was destroyed. The world-renowned golf course at the Greenbrier Resort became an extension of the nearby creek. Governor Earl Ray Tomlin declared states of emergencies for 44 counties and President Obama made a disaster declaration for the state.

Where did the rain come from?

The storms formed in an area of large temperature contrast along the northern edge of the same strong ridge of high pressure (“heat-dome”) that was responsible for the stiflingly hot temperaturesacross the U.S. Southwest. The storms then hitched a ride east along the jet stream—the area of strong winds high in the atmosphere that serves as a “storm highway”—wringing out the moist atmosphere as it went, unleashing round after round of thunderstorms and resulting in the historic rainfall totals observed in West Virginia. Scientists will likely analyze the event in further detail to determine all of the atmospheric factors that led to such a long-lasting and wet event at this location.

Your daily climate connection…

West Virginia is no stranger to extreme rain and floods. According to a U.S. Geological Surveyanalysis from 1998, every county in the state had been declared a federal flood disaster area at least once since 1967. Some of them—including many of those devastated in the June 2016 floods—have been declared so as many at ten times.

A West Virginia family talks to a Red Cross worker in front of a pile of debris from flooded homes in the town of Clendenin. Photo from the National Guard Bureau Chief’s Flickr photostream. Used under a CC license.

It’s an existing problem that climate change may make worse. According to the National Climate Assessment, heavy downpours have increased nationally over the past three to five decades, especially in the Midwest and Northeast (which, in their analysis, includes West Virginia). The trend is expected to continue: warming temperatures due to climate change are projected to increase extreme precipitation for all U.S. regions.

For mountainous regions like West Virginia, increases in extreme precipitation also mean a greater flood risk, especially in valleys where water collects. As the current flooding has shown, the power of water can be immense, destroying lives and livelihoods even with advanced warning.